Michael Menaker (19th May 1934 – 14th February 2021)

Personal Reflections on a Remarkable Life by Russell Foster

Many of you will have already heard the deeply sad news that Mike Menaker died on Sunday 14th February, 2021. I was profoundly lucky to have Mike as both a close friend and academic mentor, and in that capacity, I was asked to provide some personal reflections about Mike and his science. Part of my motivation for writing this piece is to encourage the EBRS community to share their stories and reflections about Mike so that those who never knew Mike, or who did not know him well, will get a sense of how truly remarkable he was.

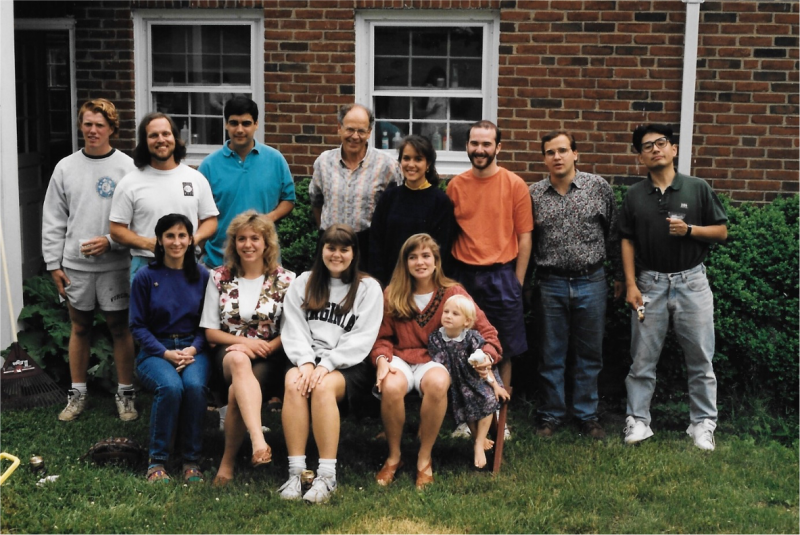

Mike (standing next to Iggy Provencio) and the “Lab Family” at a BBQ in Charlottesville, 1994

I first met Mike as an undergraduate, and as a volunteer helper at a major meeting on biological rhythms organised by Brian Follett at the University of Bristol in 1980. I had been recording the light responses from the pineal organ of Xenopus tadpoles as part of my final year project, and I was keen to show Mike the data. I had never met him, but was immersed in the wonderful papers Mike had written on “extraretinal photoreceptors”, and had been told by Brian this was one of the most brilliant thinkers in the field. I was anxious at our first meeting. I started our conversation by thanking him for making the time to see me, and apologised for potentially wasting his time. Immediately Mike said “please stop apologising. I really want to see your data”! Later I would learn, and would witness on so many occasions, that this was characteristic of Mike. It did not matter who you were, he would listen to what you had to say and engagecompletely in your science. In discussion, Mike encouraged, and gently corrected if he disagreed, saying “well, I’m not so sure about that”, before suggesting something more sensible. Mike had the capacity to inspire young minds like no other colleague I have met. His lectures were some of the best and most engaging talks delivered in our field. One of Mike’s many lasting legacies is the number of young scientists he inspired, who later made their careers in our field.

Mike, with his wonderful wife Shirley, returned to Bristol to do a sabbatical in Brian Follett’s group in the mid-1980’s, and this was the start of our friendship, and a friendship that ultimately led to an invitation to move to the University of Virginia and set-up my first lab. I spent eight immensely happy years working with Mike and the members of his team. He made you feel that you were a valued member of a family. Mike rarely ever told you what you should do, rather he would make you think about what you ought to do. Research was guided and not dictated. Mike was an ideas factory, but not all his ideas were brilliant. He was fallible and not an oracle, and Mike was the first to acknowledge this. He expected you to challenge him, and at some level he did not want you to agree. Somehow, he gave you the confidence to question and contest his ideas. He revelled in, and stimulated discussion. Mike always said “ideas are cheap”, which is technically correct but ignored the fact that an idea from Mike was invariably a gem that just needed that last bit of polishing.

Mike and Shirley Menaker in their new home in Charlottesville, 1987

Mike was not a “hands-on” scientist and rarely undertook lab work. He embraced technology but was not an end user. However, Mike grasped the utility of new technologies and how they could be used to address interesting questions. I once joked with him that his knowledge of molecular biology “encompassed the entire breadth of the subject all the way from A to B”, yet it was Mike and Martin Ralph who discovered the first clock mutant in a mammal, the tau-mutant hamster, in 1988. Then, working with Joe Takahashi, published in 2000 that the tau mutation was located in casein kinase I epsilon (CKIepsilon), a homolog of the Drosophila clock gene double-time. He knew where an observation could lead and developed the collaborations that delivered exciting new science.

On occasions Mike could be helpfully bullish. I went to Mike after my first major grant submission to the National Eye Institute (NEI), exploring the possibility of a “third ocular photoreceptor”, was kicked into the outer darkness, with not the slightest hope of funding. He was sympathetic and said very simply, “they are idiots, just turn it around to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)”. I did as advised, not convinced that the strategy would work. But several months later the same grant came top of the study section and copies were taken by NIMH to the Society for Neuroscience (SfN) annual meeting as an example of how a research grant should be written. Mike’s advice, and confidence in the data, quite simply changed my career. Mike was very much of the view that you design the best experiments, and then collect the best data you can. You stick by your data. However, if the data change, you change your hypothesis. Mike had no room for dogma. The data always had to lead and an often-used expression by Mike, that many of us will remember, was “show me the data”!

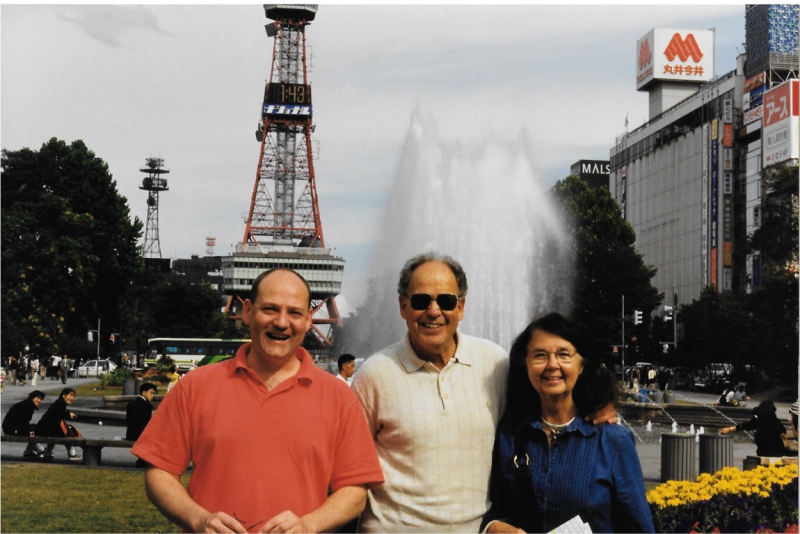

With Mike and Shirley Menaker in Sapporo Japan, 1997.

A favourite question Mike often asked, in either discussion or following a talk, would be “why?”. Mike was fascinated by questions such as: “Why” do birds show such diversity in their circadian organisation, and why do closely related species use different photoreceptors, clocks and signalling pathways? Such discussions sent me off to study the eight closely related species, but ecologically diverse, Anolis lizards of Puerto Rico. But that’s another story! Attempting to place a mechanistic understanding of circadian biology into an evolutionary and ecological context was deeply important to Mike, and he was genuinely puzzled when little or no previous thought had been given to the question by a researcher.

Work in the lab was frequently followed by parties and dinners where talk of science merged with history, philosophy, music and laughter. Lots of laughter, and all were embraced. These were inclusive events where partners, friends, and very often international visitors would all mingle, and maybe drink a beer in the hot-tub or by the pool! Mike and his wife Shirley were generous hosts, and a deeply loving couple. There was a kindness and gentleness about their relationship that touched all who met them. You wanted to be in their company and it was a joy that Shirley accompanied Mike so often to scientific meetings. If you dropped-in on them at home, Shirley would open a good bottle of Vouvray, her favourite white wine, and break out the cheese and crackers. Laughter and conversation followed, until Mike felt he should prepare supper. Mike was the cook, and it was a standing joke that Shirley could not boil an egg, or indeed a kettle, without help. Shirley’s untimely death from cancer could have snuffed out all the joy from Mike’s life, but his children and grandchildren sustained him with undiluted love until the very last.

Brian Follett, Margien Raven, Jasper Bosman, Mike and Achim Kramer (from left to right) at the EBRS Meeting in Oxford, 2011.

In more recent years, when Mike was in his 70’s and 80’s many of us urged Mike to write the definitive book on vertebrate circadian rhythms, latterly he was warming-up to the idea, but initially he strongly dismissed the notion, saying “Why would I write a book when I could use the time to write grants and papers”. It was always the ideas and the data that mattered most to Mike, and organising published work into the chapters of a book just did not excite him.

My last conversation with Mike, over the telephone, turned full circle to our first meeting - with a discussion of the pineal organ – but in this case the parietal eye of the New Zealand Tuatara. Mike was seriously ill and tired but his enthusiasm surfaced and we agreed that it would be incredibly exciting to work on this photoreceptor organ, and discover what it does in this ancient lineage of the reptiles. His enthusiasm had carried him beyond the immediate and transported him to New Zealand and another set of experiments.

Mike Menaker in his beloved, and restored, MG Circa 1994

When I first came across the following thoughts by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834), it felt for me that Coleridge was describing Mike: “The first man of science was he who looked into a thing, not to learn whether it furnished him with food, or shelter, or weapons, or tools, armaments, or playwiths (amusements) but who sought to know it for the gratification of knowing”. Mike spent his life wanting to understand circadian rhythms for the “gratification of knowing”, and his more than sixty years of research, mentorship and education

established the bedrock for much of the success that our field enjoys today. Many of us will miss Mike for the simple and selfish reason that we have lost a dear friend and scientific father. But the bigger, and more bitter loss, is that Mike will no longer be there at our meetings, asking those brilliant questions and inspiring the next generation of circadian biologists.

Russell Foster

Past President, European Biological Rhythms Society (EBRS)

Russell Foster

Past President, European Biological Rhythms Society (EBRS)